If you are reading this article, you likely know that there are already numerous image formats that we can use for the web, including the ubiquitous JPG and GIF, as well as PNG, and more recently WEBP and AVIF.

And knowing this, you might also be wondering why in the world we need yet another?

It is a good question, and one worth asking, but also one worth digging into before rushing to an answer.

So what is JPEG XL?

JPEG XL is an open-standard image format that was created with the intention of replacing the well-known JPG image format.

In 2018, the Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) issued a call for proposals for the “next-generation image compression”. Numerous proposals were submitted, but only two were selected to proceed, one by Cloudinary (FUIF) and one by Google (PIK).

The two were eventually combined to create JPEG XL (often shortened to JXL), which was standardized in 2022.

The first part of the JPEG XL name comes from the founding committee name (Joint Photographic Experts Group, or JPEG), while the X comes from a series of standards that were created leading up to the new format (namely JPEG XT/XR/XS), and the L stands for "long-term", indicating the hope that this format would become a long-term solution for the web’s image needs.

The JXL format supports both lossy (similar to JPG) and lossless (similar to PNG) compression, as well as animation (similar to GIF) and transparency (similar to GIF and PNG), but uses a new modular compression method to improve upon all of these other image formats.

Other benefits of JPEG XL

In addition to JXL combining a lot of features from multiple other image formats, JXL also improves upon many of the other image format capabilities, including:

- Increasing the number of colors available

- Increasing image quality

- Decreasing image size

- Offering progressive image loading

- Improving image coding and decoding speeds

But do we really need another image format?

There is no question that the JXL format would offer improvements in image format compression and combine a lot of features from other image formats. But JXL does not offer any new features to web imagery. That is, although it may do what other images already do better, it does not offer anything that other image formats don’t.

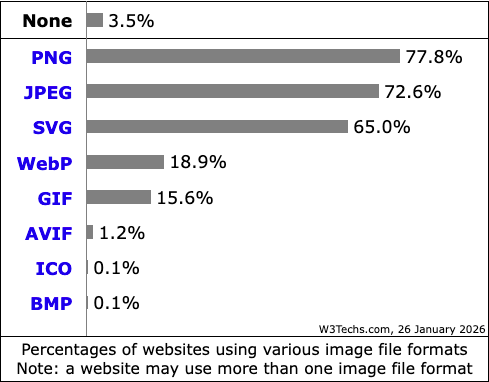

But as stated earlier, we do already have several image formats available to us. And while JPG and GIF once ruled the web, PNG has managed to overtake JPG as the predominant image format on the web, and great strides have been made to push animated GIFs aside in favor of video assets for anything larger than minor decorative animated images, relegating them to mostly tracking pixels or small icons.

This chart by W3Techs shows how often websites use various image formats as of January 2026:

WEBP adoption, however, has been slow and AVIF is still but a relative child. Even though both of these formats are far superior in both compression and quality (meaning, smaller images that still look great), adoption has been slower than those in the web performance field would like to see, perhaps because they are less well known and/or understood, or just because most devices/applications tend to automatically save images as either JPG or PNG.

And as you might expect, the web shows no sign of reducing the number of images used per page. In the last 10 years, the median total home page weight has increased by more than 200%. In 2025 alone, the median request for images per page was 19 on mobile and 17 on desktop, and the median weight for those images was 911kb on mobile and 1,058kb on desktop.

So if pages are going to continue to include more and more images, perhaps it would be prudent to see if we could make each of those images smaller. This would be one way to help reduce the overall download for our users.

How does JPEG XL compare to other image formats?

Capabilities

Ignoring the formats that are lesser-used on the web, such as BMP, or are not real competitors for JXL, such as SVG and ICO, the table below compares support and features of the other common web image formats:

| Image Format | Year Introduced | Browser Support | Colors | Alpha Channel? | Animation? |

| GIF | 1987 | 97% | 256 | Yes | Yes |

| JPG | 1992 | 100% | 16.8 million | No | No |

| PNG | 1996 | 97% | 16.7 million | Yes | Yes |

| WEBP | 2010 | 96% | 16.7 million | Yes | Yes |

| AVIF | 2019 | 95% | Up to 68 billion 1 | Yes | Yes |

| JXL | 2022 | 0% | Practically unlimited 1 | Yes | Yes |

1 One could question the necessity of so many colors, but including these to be thorough.

Comparing a single image across all of the image formats is not practical: Lossless image formats are best used for images like icons, where there are fewer colors used in larger blocks, while lossy image formats are best used for images like photographs, with lots of colors, usually fading into one another. And of course alpha channels (transparency) and animation create even more comparison challenges.

File Size

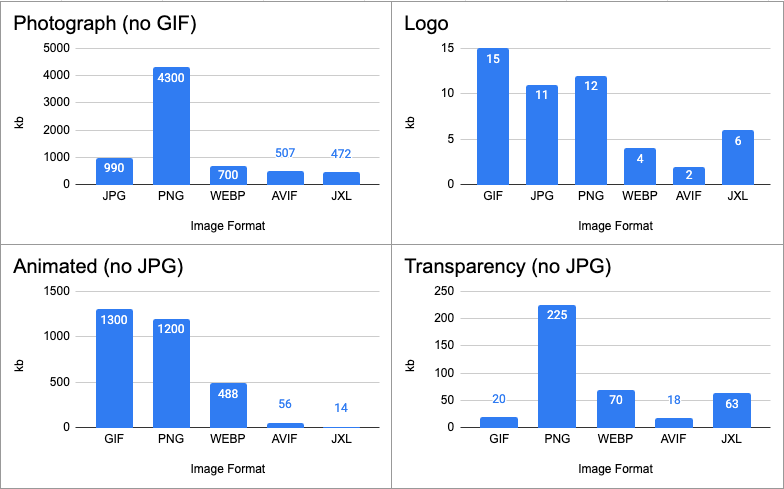

But this wouldn't be much of an article if I didn’t compare various versions, would it? So, using the four sample images below, I created versions in each of the applicable formats using (mostly) the Cloudinary suite of online image converters.

(Note: The Cloudinary online converters do not offer conversion settings, nor do they advertise what the settings being used are. It is possible that adjusting these settings would affect the converted image file size and quality.)

The images I used as starting points are:

Photograph: JPG, 990kb Credit: Unsplash | Logo: JPG, 11kb Credit: DebugBear |

Animated: GIF, 1.3MB Credit: Pixabay | Transparency: PNG, 225kb Credit: DebugBear |

The original image sizes and converted sizes are below. Conversions that resulted in a larger file size are denoted in red, conversions that result in a smaller file size are denoted in green, and the smallest converted image is green and bold:

| Image Format | Photograph | Logo | Animated | Transparency |

| GIF | N/A 1 | 15kb | 1.3MB (Initial) | 20kb |

| JPG | 990kb (Initial) | 11kb (Initial) | N/A 2 | N/A 2 |

| PNG | 4.3MB | 12kb | 1.2MB 3 | 225kb (Initial) |

| WEBP | 700kb | 4kb | 488kb | 70kb |

| AVIF | 507kb | 2kb | 56kb | 18kb |

| JXL | 472kb | 6kb | 14kb | 63kb |

1 GIF is not a suitable format for a photograph. 2 JPG does not support animated or transparent images. 3 Cloudinary does not convert to animated PNGs (APNG), so I used FreeConvert.

The above data might be a little easier to ingest via these charts (note the “N/A” variants above are excluded):

AVIF and JXL clearly win the day, neatly splitting these four image conversions.

The photograph began as a 990kb JPG and converted to a 472kb JXL, resulting in a savings of 518kb, or 52%.

The logo began as only an 11kb JPG, but JXL was able to bring that all the way down to 6kb, saving 5kb, or 44% (AVIF was even better, however, converting to only 2kb, saving 9kb, or 88%).

The animated GIF, starting at a whopping 1.3MB, converted to a mere 14kb JXL, saving an impressive 1,286kb, or roughly 99%.

And finally, the image with transparency began as a 225kb PNG, but converted down to a 63kb JXL, saving 162kb, or 72% (though AVIF was better again, converting to only 18kb, saving 207kb, or 92%).

Image Quality

The improved capabilities and file sizes of JXL are certainly important, but surely that’s meaningless if it doesn’t look as good, right?

So, here are comparisons of each original image and the converted JXL, zoomed in to see the details; the original image is always on top, the JXL conversion is always on bottom:

|  |

|  |

The photography image probably fares the best of these four conversions. At this zoom, the original and the JXL appear about equally pixelated, and the colors fairly similar.

The logo seems rather equal as well, though I can see some additional pixelation in the JXL version.

The animated JXL definitely shows pixelation that the original doesn’t, but depending on the purpose of the image, the file size savings might be worth it.

Finally, the transparency JXL seems to be the worst conversion, resulting in far less clarity in the JXL (this is where I question the conversion settings for the JXL, as it seems to lose colors, where it should be capable of far more).

While these tests will not be 100% indicative of all image conversions, clearly JXL images result in markedly improved image sizes, even in these four simple sample conversions. This means that users would need to download less, so they should see our content faster. This also means less storage cost, and reduced bandwidth, for website owners.

But can we use this new thing?

Browser and platform support for JPEG XL

While many well-known Internet companies showed initial support, including Facebook, Adobe, Intel, The Guardian, Flickr, Shopify and more, Google’s initial backing for the new format soon came into question as support was removed from the Chrome browser in 2022, less than a year after it was added.

Browsers

Then in January 2026, Chrome added decoding support back into Chromium, but to date still no version of any Chromium browser supports the image format in the wild.

Firefox remains neutral, citing the new format does not show sufficient improvement over the other formats that it already supports, and that the added decoder bloats their software and introduces possible security concerns.

Meanwhile, as of v17, Safari (MacOS and iOS) does offer decoding support, but does not support animated images or progressive decoding.

At the time of this writing, no other major browser shows any signs of support at all.

CMS

Several CMS communities express interest, but none of these have expressed any intention of adding support:

- WordPress has shown a lack of interest until browsers show more interest.

- Shopify discusses support within their forum, but does not mention the format on their Complete Guide to Image File Formats.

- Webflow also seems to show no interest, though their community also expresses interest.

- Wix shows no sign of support.

- Drupal does not appear to support the format, but their community also shows interest.

CDN

While most CDNs would allow the upload and storage of just about any static file, they also often provide image conversion services; the list below shows slow-to-no interest:

- Cloudinary certainly supports JXL, seeing as how they helped invent it!

- Fastly offers conversion to JXL via their Image Optimizer.

- AWS also does not currently offer support but their community has expressed interest.

- Akamai currently does not support JXL.

- Nor does Cloudflare.

- Or Azure.

Image Editors

Design software is also a bit of a mixed bag:

- As of version 25, PhotoShop does support importing and exporting to JXL images.

- PhotoPea currently allows opening and editing JXL images (though converted to PSDs), but exporting as JXL currently requires a plugin, while the community is showing interest in being able to export as JXL.

- Figma does not export as JXL; you would need to export as something like JPG or PNG, then use a third-party to convert to JXL.

- The same goes for Canva.

- And Framer.

- And Sketch.

- And Illustrator.

Image Converters

But there are several solid Image Converters that support creating JXL images, if you are in a position to make use of that service:

Should you use JPEG XL on your website?

There is no question that JXL images are an impressive image format, often creating smaller, crisper images, which would be great for users. And while support services like CDNs and photo editors are starting to show support, the real concern should be browser support. WEBP and AVIF have very good browser support, but JXL is not even on the map yet.

So, should you use JXL at all? The short answer is “probably not yet”.

There is certainly no harm in using them, unless you somehow only need to support iOS devices, and even then don’t need animated images or progressive decoding. Otherwise, the format just does not seem ready for prime time, while in most comparisons above, AVIF was quite on par with JXL.

Of course you can use JXL, just as long as you are also serving backup images, like using a picture element with multiple source elements, which would look something like this:

<picture>

<source srcset="image.jxl" type="image/jxl" />

<source srcset="image.avif" type="image/avif" />

<source srcset="image.png" type="image/png" />

<img

src=""

width="1600"

height="400"

alt="Always include descriptive text here"

/>

</picture>

This would allow users with supporting browsers to get the benefits of the JXL image now, while users with browsers that don't support it would cascade to something else. It’s a little more code, but hopefully you are using a template-driven environment, where you would set up your template once and not have to think about it again!

This would also serve as a great progressive enhancement opportunity, if/when JXL support ever grows, your users would just automatically start benefiting.

Image creation is the next snag. If you use a supporting CDN or image repository that can automatically create the additional image format for you, then sure, why wouldn’t you do this? But, if you have to manually create all of the various image formats that you use across your site, then I would definitely hold off for now, and stick with WEBP or AVIF, and probably still use JPG or PNG fallbacks.

So, as usual, the answer is “maybe”, and the choice is yours. But at least now, hopefully you are a little better informed on the topic, and in a better position to make that decision.

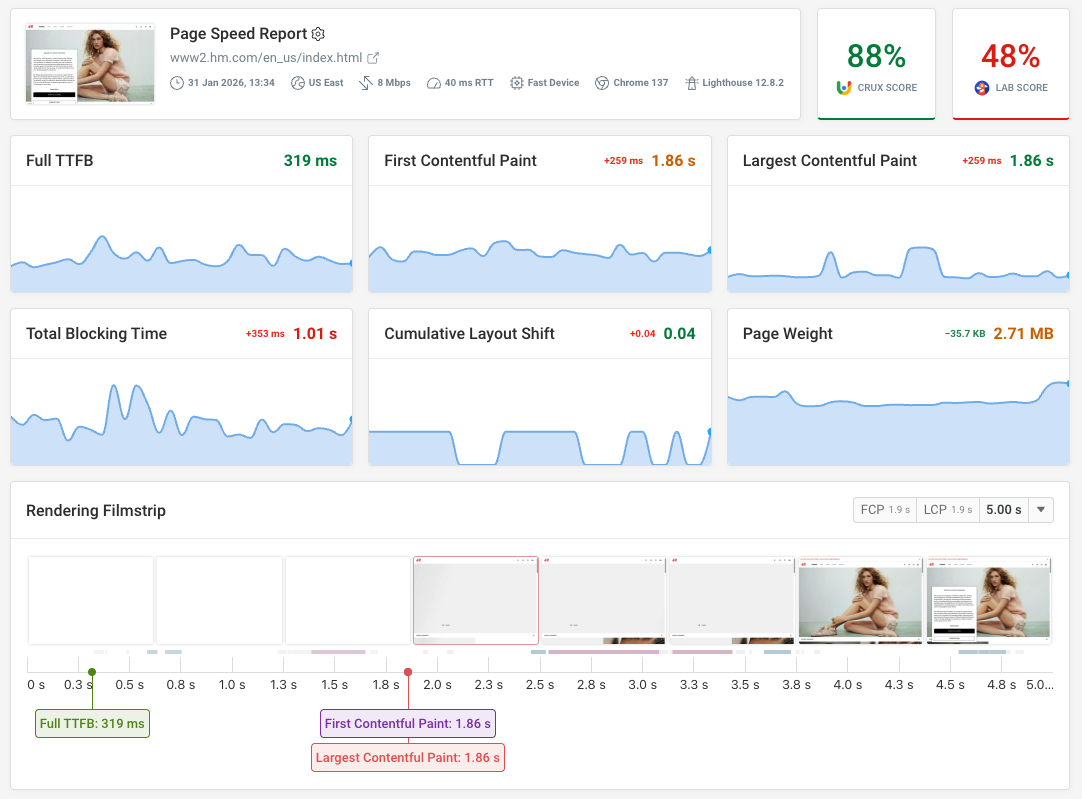

Check how images impact performance on your website

Want to make sure your website loads fast? DebugBear can help you identify whether large images or other factors are impacting user experience on your website.

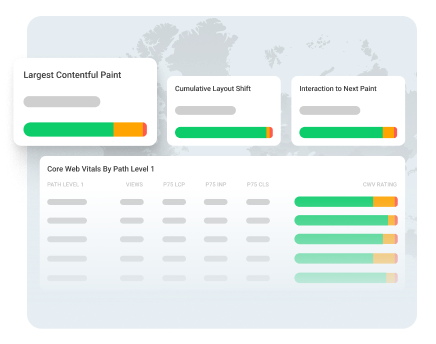

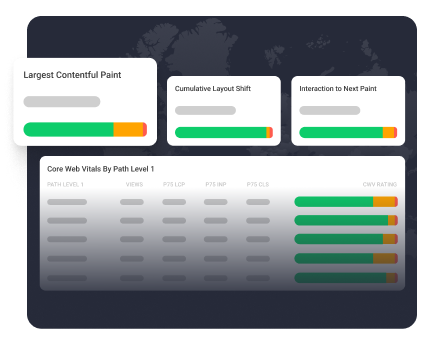

You can also track Core Web Vitals over time and get alerted when a new issue arises.

Monitor Page Speed & Core Web Vitals

DebugBear monitoring includes:

- In-depth Page Speed Reports

- Automated Recommendations

- Real User Analytics Data