The HTTP protocol lets browsers and other applications request resources from a server on the internet to load web pages. HTTP/3 is the latest version of HTTP, published by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) as the RFC 9114 standard.

HTTP3 aims to make websites faster and more secure by providing an application layer over QUIC, a next-generation transport protocol.

At a high level, HTTP3 provides the same functionalities as HTTP2, such as header compression and stream prioritization. However, under the hood, the QUIC transport protocol entirely changes the way we transfer data over the web.

In this article, we'll take an in-depth look at the new features and differences of HTTP3 vs QUIC, how they fit into the overall ecosystem of network protocols, how HTTP3 compares to the previous versions of HTTP, and the cons of the QUIC and HTTP3 protocols.

What Is HTTP3?

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is an application-layer network communication protocol of the Internet Protocol Suite, or according to its official website, the "core protocol of the World Wide Web".

It defines a request-response mechanism between client and server applications on the web that allows them to send and receive hypertext (HTML) documents and other text and media files.

HTTP3 was first known as 'HTTP-over-QUIC' because its main goal is to make the HTTP syntax and all the existing HTTP/2 functionality compatible with the QUIC transport protocol.

Thus, the new features of HTTP/3 are all coming from the QUIC layer, including built-in encryption, a new cryptographic handshake, zero round-trip time resumption on prior connections, the removal of the head-of-line blocking issue, connection migration to support mobile users on the go, and native multiplexing.

HTTP/2 is also referred to as H2 and HTTP/3 can be shortened to H3. Read our guide: HTTP/3 vs HTTP/2 Performance: Is the Upgrade Worth It?

HTTP3 vs QUIC in the TCP/IP Model

Delivering information over the internet is a complex operation that involves both the software and hardware level. One protocol cannot describe the entire communication flow due to the different characteristics of the devices, tools, and software used throughout the process.

As a result, network communication is based on a stack of communication protocols in which each layer serves a different purpose. Although there are various conceptual models that describe the structure of protocol layers, such as the seven-layer OSI Model, the internet is based on the four-layer TCP/IP model, also known as the Internet Protocol Suite. It's defined in the RFC 1122 specification as follows:

"To communicate using the Internet system, a host must implement the layered set of protocols comprising the Internet protocol suite. A host typically must implement at least one protocol from each layer."

Here is how the four layers of the TCP/IP model stack up, from top to bottom:

| Purpose | ID mechanism (examples) | Protocols (examples) | Devices/Tools (examples) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAYER 4: Application layer | process-to-process communication | application-level identification mechanisms | HTTP, DNS, TLS, FTP, SMTP, SSDP, etc. | web browsers and server applications, mail server and client applications, FTP server and client applications, etc. |

| LAYER 3: Transport layer | host-to-host communication for applications | port numbers (ports are either TCP or UDP ports; QUIC and DCCP use UDP ports) | TCP, UDP, QUIC, DCCP, etc. | network ports (each LAYER-4 protocol has its commonly used port number — e.g. HTTP uses port 80) |

| LAYER 2: Internet layer | routing (selecting a path for traffic in a network or across multiple networks) | IP addresses | IP (IPv4 and IPv6), IPsec, etc. | network interface controllers (NICs) — internal or external |

| LAYER 1: Link (network interface) layer | moving network packets between different hosts on the same local network | MAC (Media Access Control) addresses | IEEE 802 standards for LAN/MAN/PAN networks (Ethernet, Wi-Fi, etc.), PPP, etc. | device drivers for NICs — e.g. PHY chips for Wi-Fi, Ethernet devices, etc. |

As the above table shows, HTTP is an application-layer protocol that makes communication possible between two software applications: a web server and a web browser. HTTP messages (requests or responses) are delivered over the internet by a transport-layer protocol: either TCP (for HTTP/2 and HTTP/1.1 messages) or QUIC (for HTTP/3 messages) — we'll see how transport protocols work in detail later in the article.

HTTP Versions: From the Start to HTTP3 (Released in June 2022)

Like most communication protocols, H3 is defined in the RFC (Request for Comments) Series used for publishing, editing, and cataloging technical documents related to the internet.

HTTP/3 was released as RFC 9114 in June 2022. However, two previous versions of the protocol, HTTP/2 and HTTP/1.1 are still in active use.

Here's a brief summary of the evolution of the HTTP protocol:

| HTTP version | Release date | Specification | Status | Key features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTTP/0.9 | 1991 | has no RFC number; see the original doc created by Tim Berners-Lee | historical (not in use) | only raw data transfer introduced the TCP/IP model and GET requests (also called the 'one-line protocol') |

| HTTP/1 | 1996 | RFC 1945 | historical (not in use) | introduced HTTP status codes, Content-Type, the POST and HEAD methods, and request headers |

| HTTP/1.1 | 1997 | RFC 9112 | Internet Standard | update to HTTP/1; introduces the Host header, the 100 Continue status, persistent connections, and new HTTP methods (PUT, PATCH, DELETE, CONNECT, TRACE, OPTIONS) |

| HTTP/2 | 2015 | RFC 9113 | Proposed Standard | introduces a new binary framing layer that's not compatible with HTTP/1.1 and request and response multiplexing, stream prioritization, automatic header compression (HPACK), connection reset, server push |

| HTTP/3 | 2022 | RFC 9114 | Proposed Standard | makes HTTP compatible with QUIC, moves from TCP to UDP transport |

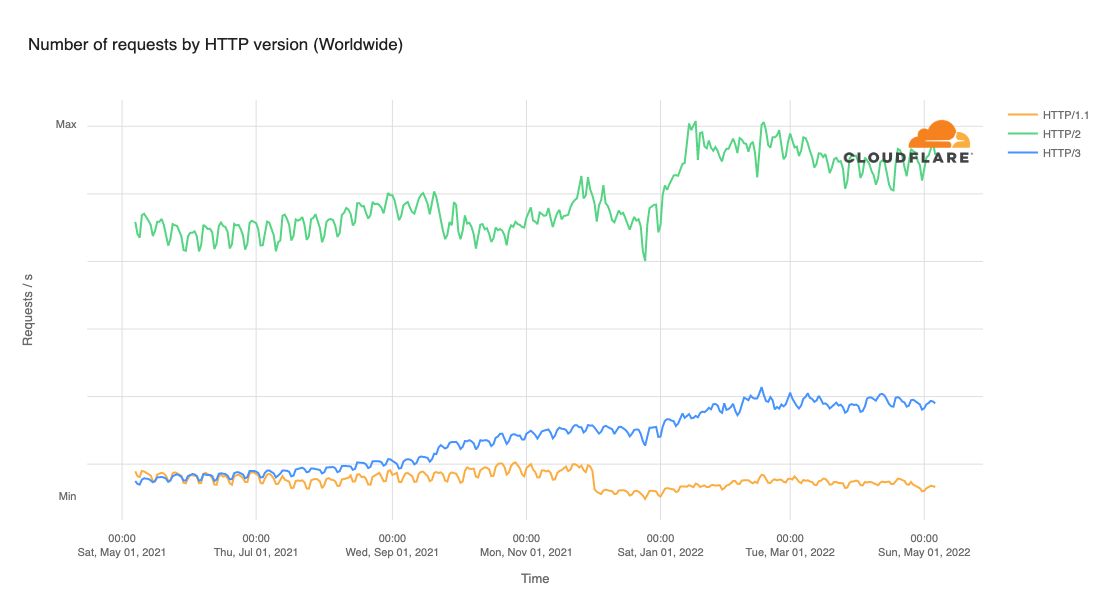

See Cloudflare Radar for the current usage data of the three active versions of HTTP — 28% of Cloudflare's traffic is already transferred via HTTP/3 and QUIC.

While most requests on Cloudflare's global network still use HTTP/2, HTTP/3 traffic surpassed HTTP/1.1 in July 2022:

Image credit: Cloudflare Blog

The QUIC Protocol Explained

QUIC (not an acronym; pronounced as 'quick') is a general-purpose transport-layer protocol published as an IETF Proposed Standard in 2021 — one year before H3. It can be used with any compatible application-layer protocol, but HTTP/3 is its most frequent use case.

QUIC runs on top of another transport protocol called UDP, which is responsible for the physical delivery of application data (e.g. an H3 message) between the client and server machines. UDP is a quite simple and lightweight protocol, which means that it's fast, but on the other hand, it lacks many features essential for reliable and secure communication. QUIC implements these higher-level transport features, so the two protocols work together to optimize the delivery of HTTP data over the network.

UDP has been around for more than 40 years — it was standardized back in 1980. The acronym stands for User Datagram Protocol as UDP exchanges connectionless datagrams (basic transfer units) between two end machines.

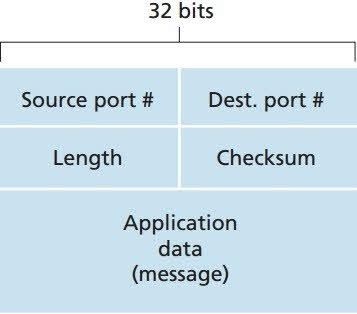

This is what a datagram looks like — it doesn't include any data related to connection establishment or information about the success of delivery. It only includes a lightweight header and the message:

Image credit: The Network Encyclopedia

As you can see above, a UDP header is very lightweight: only 64 bits altogether (16 bits for the source port, 16 bits for the destination port, 16 bits for the length of the message, and 16 bits for the checksum). This makes pure UDP delivery very fast — however, QUIC makes delivery slower with the implementation of additional features.

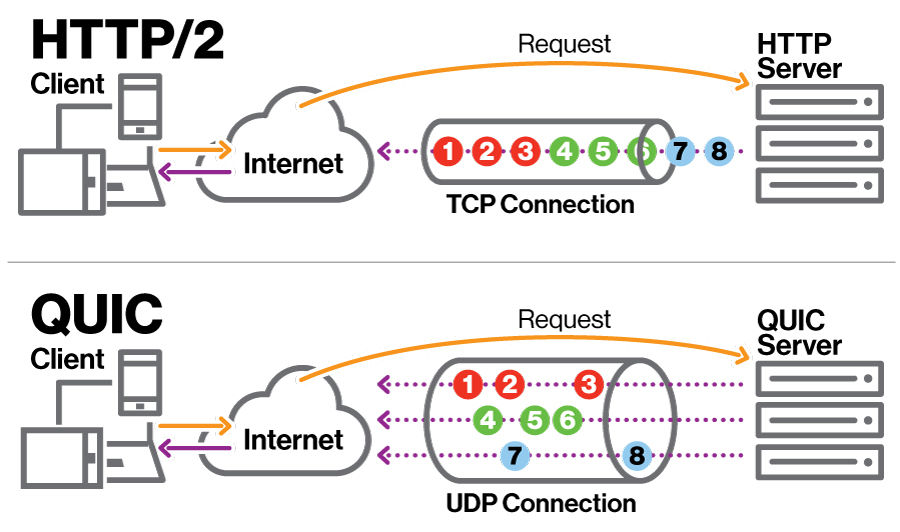

With version 3, HTTP moves from TCP-based to UDP-based connections. As a result, the entire underlying structure of network communication changes.

The TCP vs UDP Protocols

Like UDP, TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) is not a new transport protocol. It was created by two DARPA scientists in 1974 (first documented as RFC 675; the current version is standardized as RFC 9293).

It uses a different, connection-oriented, reliable approach to data transport that's slower than the connectionless and fast but unreliable UDP. With UDP, we don't know whether the packet has been delivered as it has no built-in feedback mechanism while with TCP, every dropped packet is retransmitted.

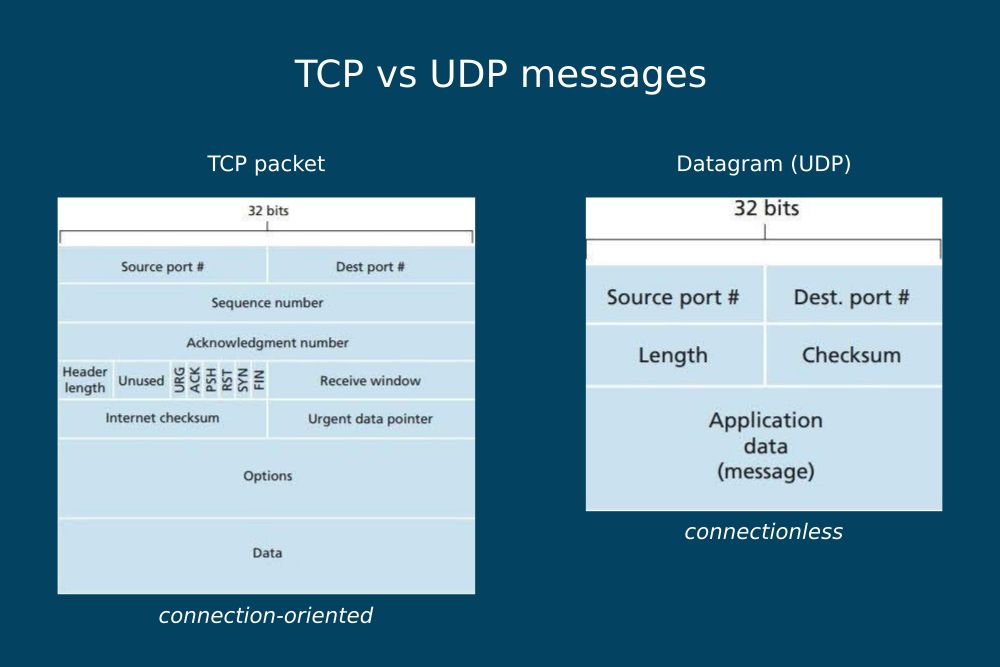

The diagram below shows the structure of a TCP packet and a UDP datagram side by side. For more information, see this TCP vs UDP comparison table by GeeksforGeeks:

Image source: The Network Encyclopedia

As you can see in the diagrams above, a TCP packet includes all the information necessary for performing the SYN/SYN-ACK/ACK handshake that establishes a reliable connection between the client and server. On the other hand, a UDP datagram only consists of a 64-bit header and the message.

The main advantage of UDP is its connectionless nature — as there's no established connection between the client and server, network packets can use different delivery routes. In this way, each packet can use the most optimal path that's available at that moment.

However, unlike TCP, UDP doesn't guarantee delivery, which is its main shortcoming. As it has no loss detection mechanism, if a datagram doesn't reach its destination, it's simply dropped. Plus, as packets are delivered independently of each other, they arrive at their destination out of order.

What Is QUIC Used For?

QUIC was created to replace TCP with a more flexible transport protocol with fewer performance issues, built-in security, and a faster adoption rate (we'll see this feature in detail in the Resistance to Protocol Ossification section below). It needs UDP as a lower-level transport protocol primarily because most devices only support TCP and UDP port numbers.

In addition, QUIC leverages UDP's:

- connectionless nature that makes it possible to move multiplexing down to the transport layer and removes TCP's head-of-line blocking issue (we'll see this in detail later)

- simplicity that allows QUIC to re-implement TCP's reliability and bandwidth management features in its own way

QUIC transport is a unique solution. While it's connectionless at the lower level thanks to the underlying UDP layer, it's connection-oriented at the higher level thanks to its re-implementation of TCP's connection establishment and loss detection features that guarantee delivery. In other words, QUIC merges the advantages of both types of network transport.

It has another important purpose as well — implementing an advanced level of security at the transport layer. QUIC integrates most features of the TLS 1.3 security protocol and makes them compatible with its own delivery mechanism. In the HTTP/3 stack, encryption is not optional but a built-in feature.

Here's a recap of how the three transport-layer protocols, TCP, UDP, and QUIC, compare to each other:

| TCP | UDP | QUIC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layer in the TCP/IP model | transport | transport | transport |

| Place in the TCP/IP model | on top of IPv4 or IPv6 | on top of IPv4 or IPv6 | on top of UDP |

| Connection type | connection-oriented | connectionless | connection-oriented |

| Order of delivery | in-order delivery | out-of-order delivery | out-of-order delivery between streams, in-order delivery within streams |

| Guarantee of delivery | guaranteed (lost packets are retransmitted) | no guarantee of delivery | guaranteed (lost packets are retransmitted) |

| Handshake mechanism | non-cryptographic handshake | no handshake | cryptographic handshake |

| Security | unencrypted | unencrypted | encrypted |

| Data identification | knows nothing about the data it transports | knows nothing about the data it transports | uses stream IDs to identify the independent streams it transports |

HTTP/1.1 vs HTTP/2 vs HTTP/3 Protocol Stacks: Main Differences

Now that we looked into the differences and similarities of the TCP vs UDP vs QUIC transport protocols, let's see the main differences between the three HTTP stacks.

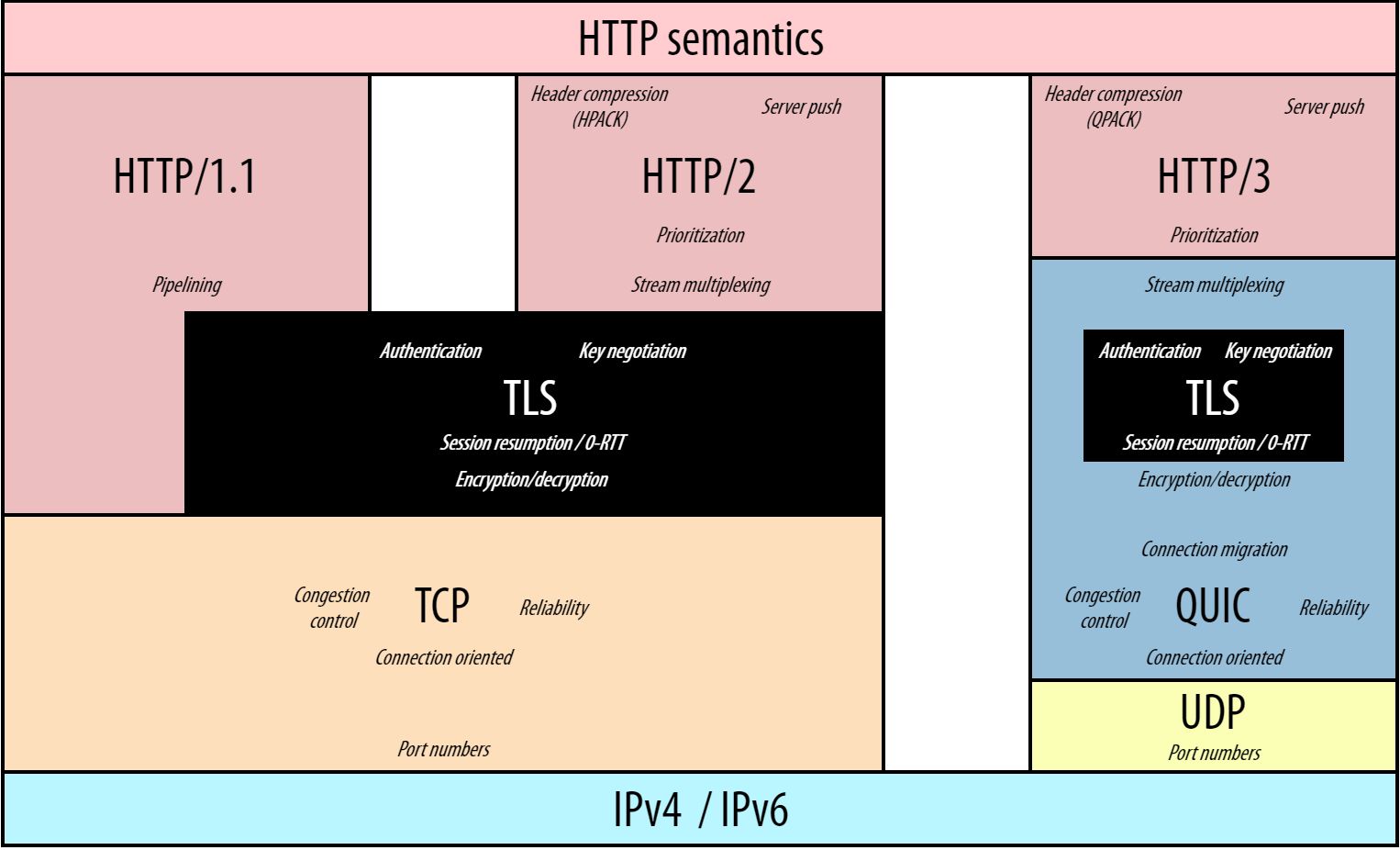

As discussed above, H3 comes with a new underlying protocol stack that brings UDP and QUIC to the transport layer. However, there's another important change. As you can see in the diagram below, some of the roles and features of the application and transport layers also change:

Image credit: Robin Marx: H3 Protocol Stack; GitHub

Image credit: Robin Marx: H3 Protocol Stack; GitHub

The most important differences between the HTTP/3-QUIC-UDP stack and the TCP-based versions of HTTP communication are as follows:

- QUIC integrates most features of the TLS 1.3 security protocol, so encryption moves down from the application layer to the transport layer (we'll discuss this in the next section in detail).

- HTTP/3 doesn't multiplex the connection between different streams as this feature is performed by QUIC at the transport layer — transport-layer multiplexing removes the head-of-line blocking issue present in HTTP/2 (HTTP/1.1 doesn't have this issue because it opens multiple TCP connections and offers the option of pipelining instead of multiplexing, which turned out to have serious implementation flaws and was replaced with application-layer multiplexing in HTTP/2).

- The UDP layer is more lightweight than the TCP layer because the latter has much more functionalities. In the HTTP/3 stack, QUIC is responsible for connection establishment, congestion control, and loss detection, which are handled by TCP in the two previous stacks.

- The QUIC layer has many responsibilities: it reimplements TCP's features, integrates the TLS security protocol, and adds some new features, e.g. connection migration, to the transport layer.

Run A Free Page Speed Test

Test Your Website:

- Automated Recommendations

- Detailed Request Waterfall

- Web Vitals Assessment

7 Best Features of HTTP/3 and QUIC

The new features in HTTP/3 and QUIC can help make server connections faster, more secure, and more reliable.

Even though the features below are frequently referred to as the features of H3, most of them come from the QUIC layer. As mentioned above, HTTP/3 simply provides the application layer on top of these transport-layer features.

Note that the following section only includes a selection of the features of HTTP/3 and QUIC. For the full feature list, consult RFC 8999, 9000, 9001, and 9002 for QUIC and RFC 9114, 9204, and 9218 for HTTP/3.

The features discussed in the HTTP3 specifications, such as the QPACK header, are not new features per se; they only make HTTP2's application-layer functionality compatible with the underlying QUIC transport.

1. The QUIC Handshake

HTTP2 needs at least two round-trips between the client and server to execute the handshake process: one for the TCP handshake for connection establishment and at least one for the TLS handshake for authentication (depending on the TLS version).

As QUIC combines these two handshakes into one, HTTP3 only needs one round-trip to establish a secure connection between the client and server. The result is faster connection setup and lower latency.

QUIC integrates most features of TLS 1.3, the latest version of the Transport Layer Security protocol, which means that:

- The encryption of HTTP/3 messages is not optional like with HTTP/2 and HTTP/1.1, but mandatory. With HTTP/3, all messages are sent via an encrypted connection by default.

- TLS 1.3 introduces an improved cryptographic handshake that requires just one round-trip between the client and server as opposed to TLS 1.2's two round-trips for authentication — (see the difference between a TLS 1.2 and a TLS 1.3 handshake).

- QUIC integrates this with its own handshake for connection establishment, which replaces the TCP handshake.

- As HTTP/3 messages are encrypted at the transport level, more information is secured than before:

- In the HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 stacks, TLS runs in the application layer, so only the HTTP data is encrypted while the TCP headers are sent as plain text, which comes with some security risks.

- In the HTTP/3 stack, TLS runs in the transport layer (inside QUIC), so not only the HTTP message is encrypted but most of the QUIC packet header too (except some flags and the connection ID — see later in the article).

In short, HTTP/3 uses a more secure transport mechanism than the previous, TCP-based versions of HTTP.

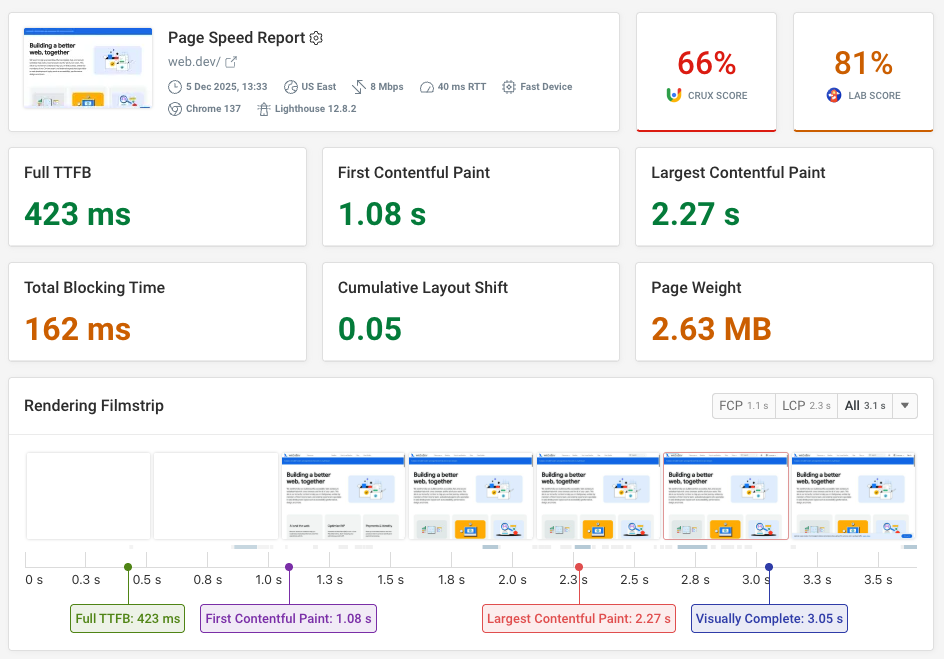

Here is how the structure of the TLS 1.3 handshake compares to the QUIC handshake:

As you can see in the diagram below, QUIC keeps TLS 1.3's content layer that includes the cryptographic keys but replaces the record layer (responsible for fragmenting the data into smaller blocks/records to prepare it for transmission) with its own transport functionality:

Image source: RFC 9001

Image source: RFC 9001

2. 0-RTT on Prior Connections

On pre-existing connections, QUIC leverages the 0-RTT feature of TLS 1.3.

0-RTT stands for zero round-trip time resumption, which is a new performance feature of the TLS protocol, introduced in version 1.3.

With 0-RTT resumption, the client can send an HTTP request in the first round-trip on prior connections because the cryptographic keys between the client and server have already been negotiated — data sent on the first flight is called early data.

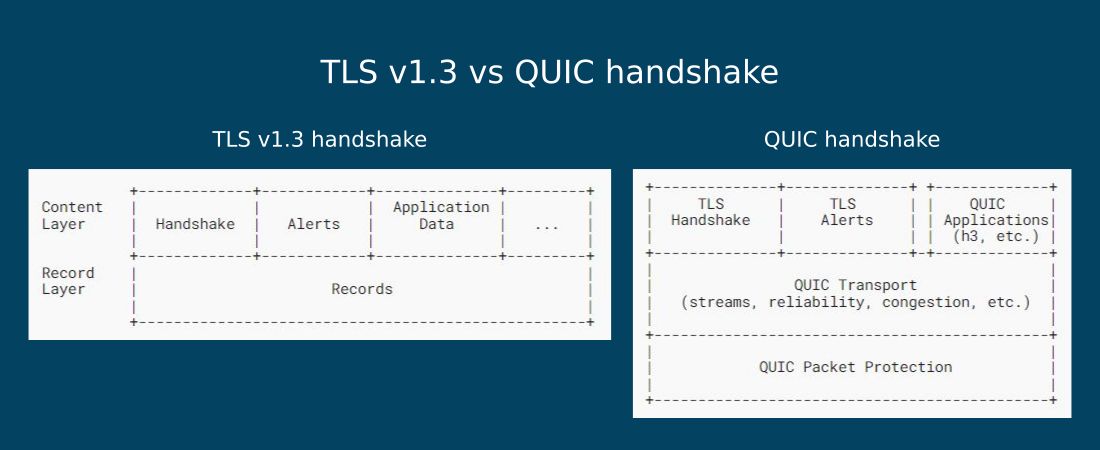

The diagram below shows how the H2 and H3 stacks compare in terms of connection setup:

- If you use HTTP2 with TLS 1.2, the client can send the first HTTP request in the fourth round-trip.

- With HTTP2 and TLS 1.3, the first request for application data can be sent in the third or second (on prior connections) round-trip.

- With HTTP3 and QUIC, which includes TLS 1.3 by default, the first HTTP request is sent in the second or first (on prior connections) round-trip.

3. Head-of-Line Blocking Removal

As the HTTP/3 protocol stack has a different structure than HTTP/2, it removes HTTP/2's biggest performance problem: head-of-line (HoL) blocking. This issue happens when a packet is dropped on an HTTP/2 connection. Until the lost packet is retransmitted, the entire data transfer process stops and all the packets have to wait on the network, which leads to longer page load times.

In HTTP/3, head-of-line blocking removal is made possible by native multiplexing, one of QUIC's most important features.

HoL blocking terminology

To understand what head-of-line blocking is and why QUIC only has non-blocking byte streams, let's see the most important concepts related to this phenomenon:

Byte stream

A byte stream (or just stream) is a sequence of bytes (units of eight binary digits/bits) sent over a network. Bytes are transported as packets of different sizes — e.g. the minimum size of an IPv4 packet is 20 bytes while its maximum size is 65,535 bytes (an IP packet can carry a UDP datagram or a TCP segment). A byte stream is essentially the physical manifestation of a single resource (file) sent over the network.

Multiplexing

Multiplexing makes it possible to deliver multiple byte streams over one connection, which means that the browser can load multiple files on the same connection simultaneously.

While HTTP/1.1 doesn't support multiplexing (it opens a new TCP connection for each byte stream), HTTP/2 introduces application-layer multiplexing (it opens just one TCP connection and sends all the byte streams over it), which results in head-of-line blocking.

Head-of-line blocking

Head-of-line blocking is a performance issue caused by TCP's byte stream abstraction. TCP doesn't have any knowledge about the data it transports and sees everything as a single byte stream. So when a packet is dropped anywhere on the network, all the other packets on the multiplexed connection stop delivering and wait until the lost one is re-transmitted — even if they belong to a different byte stream.

As TCP uses in-order delivery, the lost packet blocks the entire delivery process at the head of the line. At a higher rate of packet loss, this can significantly harm site speed. Even though multiplexing was introduced as a performance optimization feature to HTTP/2, at a 2% packet loss, HTTP/1.1 connections are usually faster (see more in the HTTP/3 Explained GitBook by Daniel Stenberg).

Native multiplexing

In the HTTP/3 protocol stack, multiplexing is moved down to the transport layer — this is called native multiplexing. QUIC identifies each byte stream with a stream ID, so it doesn't see black boxes like TCP but has some knowledge about the data it delivers (it only sees the stream IDs, but still doesn't know what files it delivers).

How does QUIC remove head-of-line blocking?

QUIC runs on UDP, which uses out-of-order delivery, so each byte stream is transported independently over the network (by finding the most optimal route available). However, for reliability, QUIC still ensures the in-order delivery of packets within the same byte stream so that the data related to the same request arrives in a consistent way.

As QUIC identifies each byte stream and streams are delivered on independent routes, if a packet gets lost, the unaffected byte streams don't have to wait for its re-transmission. These resources can keep downloading without being blocked by the lost packet at the head of the line.

Here's a diagram of how QUIC's native multiplexing compares to HTTP2's application-layer multiplexing:

Image credit: Devopedia "QUIC." Version 5, (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Image credit: Devopedia "QUIC." Version 5, (CC BY-SA 4.0)

As you can see in the diagram above, both HTTP/2 and QUIC open just one connection between the client and server, but QUIC transports the byte streams independently, on different delivery routes so that they don't block each other.

Even though QUIC eliminates the HoL blocking issue of HTTP/2, out-of-order delivery also has a downside: byte streams will not necessarily arrive in the same order they were sent in. For example, it can happen that the least important resource arrives first, and the web page can't start loading.

This additional head-of-line blocking can be mitigated by resource prioritization on HTTP clients (e.g. the browser downloads render-blocking resources first). With priority hints, you can also assign a relative priority to resources to help browsers prioritize your resources.

4. QPACK Field Compression

QPACK is a field compression format for HTTP3 that makes HTTP2's HPACK header compression format compatible with the QUIC protocol ('header' and 'field' are used synonymously; they refer to the metadata sent in the header or trailer of an HTTP message).

Field compression eliminates redundant metadata by assigning indexes to fields that are used multiple times during the connection. At a high level, HPACK and QPACK have the same functionality: both reduce the bandwidth required to transmit HTTP headers over the network. However, they use partly different mechanisms to address the different needs of the underlying transport protocols: TCP (HPACK) vs QUIC (QPACK).

How Does HPACK Work?

To reduce the size of the header, HPACK uses two indexing tables that assign indexes to fields:

- A static table, which:

- is read-only

- includes pre-defined fields that frequently occur in every HTTP message

- A dynamic table, which:

- is empty initially

- is built up over the course of the connection and updated incrementally with every request

- includes the per-message changes either literally or as a reference to a field that was sent previously

To perform the header compression, both the client and server run an encoder and decoder. The HPACK header is encoded by the sender and decoded by the receiver application. As HTTP/2 sends and receives messages in order, HPACK can safely use references in the dynamic tables as they'll always refer to a field that has already arrived.

Why Is QPACK Needed?

As opposed to HTTP2, HTTP3 cannot use the HPACK format which was created for TCP and assumes that byte streams arrive in order. If HTTP/3 used HPACK compression, it would result in additional head-of-line blocking because HPACK relies on references to previous fields.

However, with HTTP3, byte streams don't arrive in order, so it can happen that the dynamic table includes a reference to a message that hasn't arrived yet — which would make the stream wait for the referenced one.

To solve this issue, QPACK introduces two unidirectional stream types: encoder and decoder streams. In addition to the bidirectional byte streams that deliver the HTTP3 messages (including the compressed QPACK headers that also use indexes from the static and dynamic tables), the client and server can open encoder and decoder streams that deliver instructions to the other endpoint.

An encoder stream includes the encoder's instructions for the decoder while a decoder stream includes the decoder's instructions for the encoder. Each HTTP endpoint (client or server) can open one encoder and one decoder stream at most, however, they don't necessarily have to do so — for instance, if they don't want to use the dynamic table, they can avoid starting an encoder stream.

As opposed to the main bidirectional byte stream, the encoder and decoder streams are unidirectional, which means that they only deliver data in one direction without waiting for the response of the other endpoint. These are critical streams that stay open during the lifetime of the main connection and cannot be closed.

QPACK's Performance Trade-Off

While adding extra (albeit lightweight) unidirectional byte streams to the communication comes with a performance overhead, it also mitigates the additional head-of-line blocking issue between independent byte streams arising from field compression.

The QPACK specification gives a fairly high level of freedom to client and server implementations to decide individually which one is more important and to what extent: head-of-line blocking mitigation or a higher level of field compression.

5. Flexible Bandwidth Management�

Bandwidth management aims to distribute the available network capacity in the most optimal way between packets and streams. It's essential functionality because the sender and receiver machines and the network nodes in-between them (e.g. routers and switches) all process packets at different speeds that also dynamically change over time.

Managing bandwidth helps avoid data overflow and congestion over the network, which result in slower server response times and also pose a security risk (e.g. vulnerability against flood attacks).

As UDP doesn't have built-in bandwidth management, QUIC takes on this responsibility in the H3 stack. It reimplements the two pillars of TCP's bandwidth management:

- flow control, which limits the send rate at the receiver to prevent the sender from overwhelming it

- congestion control, which limits the send rate at every node on the path between the sender and receiver to prevent congestion over the network

Per-Stream Flow Control

To support independent streams, QUIC performs flow control on a per-stream basis. It controls the bandwidth consumption of stream data at two levels:

- on each stream individually, by setting the maximum amount of data that can be allocated to one stream

- across the entire connection, by setting the maximum cumulative number of active streams

Using per-stream flow control, QUIC limits the data that can be sent at the same time to prevent the receiver from being overwhelmed and to share the network capacity between the streams more or less fairly.

Note that QUIC uses a different flow control algorithm for cryptographic data used for authentication such as handshakes — this is controlled by TLS within QUIC.

Congestion Control with Optional Algorithms

QUIC allows implementations to choose from different congestion control algorithms, as these are not specific to the transport protocol.

The most well-known algorithms are:

- NewReno – the congestion control algorithm used by TCP, defined in RFC 6582, and used as an explanation of QUIC's congestion control mechanism in RFC 9002

- CUBIC – defined in RFC 8312, similar to NewReno, but uses a cubic function instead of a linear one to calculate the congestion window increase rate

- BBR (Bottleneck Bandwidth and Round-trip propagation time) – doesn't have an RFC yet; it's currently developed by Google

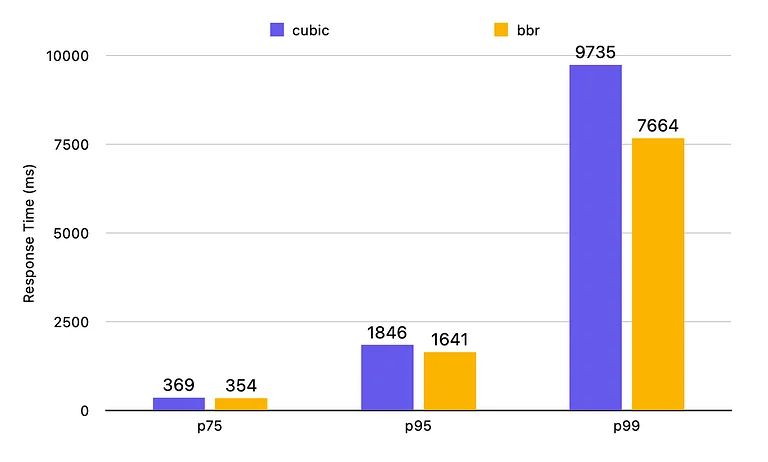

On poorer connections, there can be significant differences between the performance of different congestion control algorithms.

For example, according to the measurements of the Gumlet video streaming service, the BBR algorithm improves server response times by 21% compared to CUBIC on the slowest connections. The performance gains have the biggest impact on lossy network connections; faster connections experience less noticeable improvements.

In the chart below, you can see how the two congestion control algorithms impact server response times on lossy connections. While at the 75th percentile (on the slowest 25% of connections), BBR is just 4% faster than CUBIC, at the 99th percentile (on the slowest 1% of connections), it's 21% faster!

Image credit: Gumlet Blog, BBR vs CUBIC – Server response time on lossy connections

Image credit: Gumlet Blog, BBR vs CUBIC – Server response time on lossy connections

6. Seamless Connection Migration

Connection migration is a performance feature of QUIC that supports users who experience a network change, such as mobile users on the go. QUIC makes connection migration (more or less) seamless by making use of connection identifiers.

Connection IDentifier (CID)

By attaching an unencrypted connection identifier (CID) to each QUIC packet header, QUIC doesn't have to reset the connection like TCP if the device switches to a new network (for example, from a 4G network to Wi-Fi, or vice versa) or the IP addresses or port numbers change for any other reason.

With the help of connection migration, QUIC doesn't have to redo the handshake under the new conditions and H3 doesn't have to re-request the files that were being downloaded when the network migration happened — which can be a problem in the case of larger files or video streaming.

Note, however, that the client and server still need to re-negotiate the send rates discussed above in the 'Flexible bandwidth management' section.

Linkability Prevention

To avoid privacy issues, e.g. to prevent hackers from following the physical movement of a smartphone user by tracking the unencrypted CID across networks, QUIC uses a list of connection identifiers instead of just one.

This feature is called linkability prevention. At the beginning of the connection, the client and the server agree on a randomly generated list of connection IDs that all map to the same connection. With every network switch, a new CID from the list is attached to the QUIC header, so different networks cannot be linked to the same user.

7. Resistance to Protocol Ossification

One of the main reasons for creating QUIC, and subsequently HTTP/3, was to make a transport protocol that's resistant to protocol ossification, which is an inherent characteristic of protocols implemented in the operating system (OS) kernel, such as TCP.

OSs are rarely updated, which applies even more to the operating systems of middleboxes, such as firewalls and load balancers, which sit between the client and server but are still essential parts of the network.

Protocol ossification is a problem because it makes it hard to introduce new features, as middleboxes with an older version of the protocol don't recognize the new feature and drop the packets for security reasons. As a result, the adoption rate of new TCP features is slow. QUIC aims to solve this issue.

QUIC has a higher resistance to protocol ossification than TCP for three reasons:

- It runs in the user space (where native apps run) instead of the kernel, so it's easier to deploy new implementations.

- It has a higher level of encryption (e.g. most of the QUIC header is encrypted), so middleboxes can't read the content of the packet, therefore don't drop them — which frequently happens to TCP packets that include a newer feature that middleboxes with older operating systems don't recognize and deem a security risk.

- UDP is supported by every device, and the new features are added by the QUIC layer — on the other hand, adding new features via TCP extensions frequently requires an operating system update.

That said, QUIC streams can still be dropped for different reasons (we'll see some of these in the next section), but the adoption of new QUIC features will be faster than TCP.

4 Worst Problems of HTTP3 and QUIC

While the H3 protocol stack has several advantages, such as built-in encryption, head-of-line blocking reduction, 0-RTT connection setup on existing connections, and others, it also comes with some limitations.

1. Performance Gains Depend on the Implementation

While the QUIC specifications give a lot of freedom to implementation developers, it's still hard to correctly implement the features. For example, connection migration is great functionality, but many implementations don't include it yet due to the complexity of its practical implications. Or, if a client implementation makes a poor choice of multiplexing algorithm, it can cause additional head-of-line blocking.

A research paper by Alexander Yu and Theophilus A. Benson also found that it's difficult to deal with QUIC's edge cases and properly implement congestion control algorithms. For now, HTTP's real-world performance gains are not so high and show inconsistency across different implementations (in other words, it's hard to tell why an implementation performs better under certain conditions than another one).

For more information on this subject, check out IETF's list of all known QUIC implementations.

2. HTTP Version Negotiation Is Required Before Using H3

HTTP3 generally doesn't work for the first request because browsers assume by default that the server doesn't support HTTP3 and send the first request via either HTTP2 or HTTP/1.1 on a TCP connection.

If the server supports HTTP3, it responds with an Alt-Svc (Alternative Service) header that informs the client that it can send HTTP3 requests. The browser can respond in different ways: it can open a QUIC connection right away or wait until the TCP connection is closed.

Either way, an HTTP3 connection is only set up after the initial resources have been downloaded over an HTTP/1.1 or HTTP2 connection.

3. Network Management Gets Harder

As QUIC encrypts not only the payload but also most of the packet metadata, it becomes more difficult to troubleshoot network errors and optimize networks for performance and security, which makes the job of network engineers more challenging. Setting up blocking and reporting rules becomes harder for the same reason too.

Because of the high level of encryption, providing firewalling and network health tracking services also gets more difficult than for TCP streams that come and go with unencrypted metadata in the header. Due to this and the increased level of complexity, many firewalls don't support QUIC yet, which creates a security risk for organizations that rely on these services.

4. Some Networks Block UDP

As UDP has historically been used for different kinds of cyberattacks (e.g. denial-of-service type of attacks), 3 - 5% of networks block UDP, except for essential UDP traffic such as DNS requests.

If UDP is blocked on a network, the traffic falls back to TCP-based HTTP/2 connections. However, as RFC 9308, which discusses the applicability of QUIC, warns, "any fallback mechanism is likely to impose a degradation of performance and can degrade security".

Learn More about HTTP/3 and QUIC

HTTP/3 and QUIC are extensive topics that are documented in several RFC documents (see a list of the most important RFCs related to HTTP/3 and QUIC on my blog).

For more knowledge on the subject, watch David Bombal's discussion with Robin Marx on YouTube or Robin's HTTP/3 talk at SmashingConf.

Wrapping Up

HTTP3 and QUIC change the way we use the internet by introducing a new, UDP-based protocol stack that makes use of independent streams and comes with built-in encryption and a new type of cryptographic handshake.

In theory, using HTTP3 comes with many advantages related to performance, security, and connectivity, but in practice, it still needs time to be properly implemented and widely adopted.

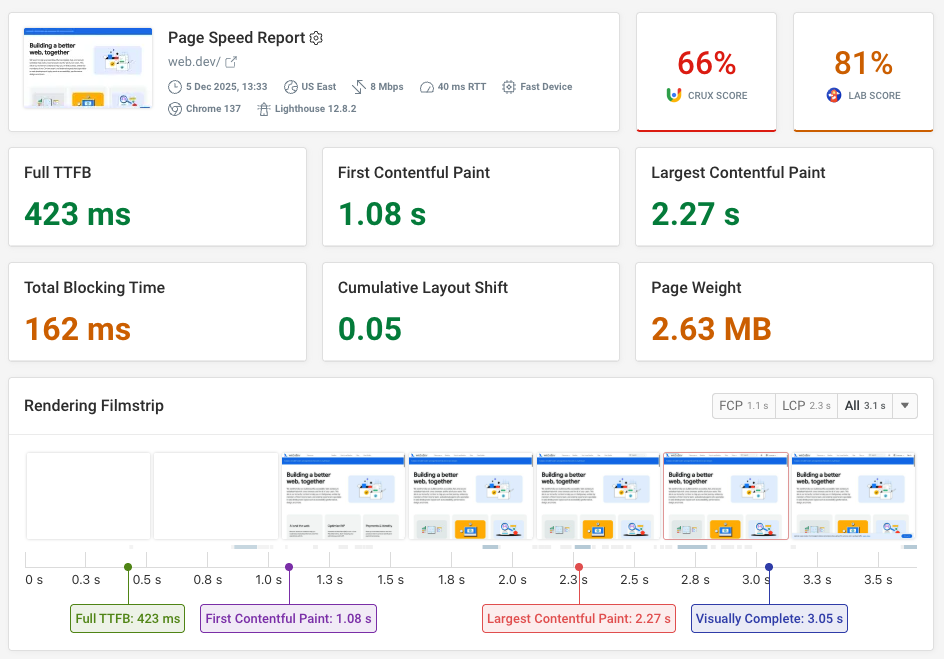

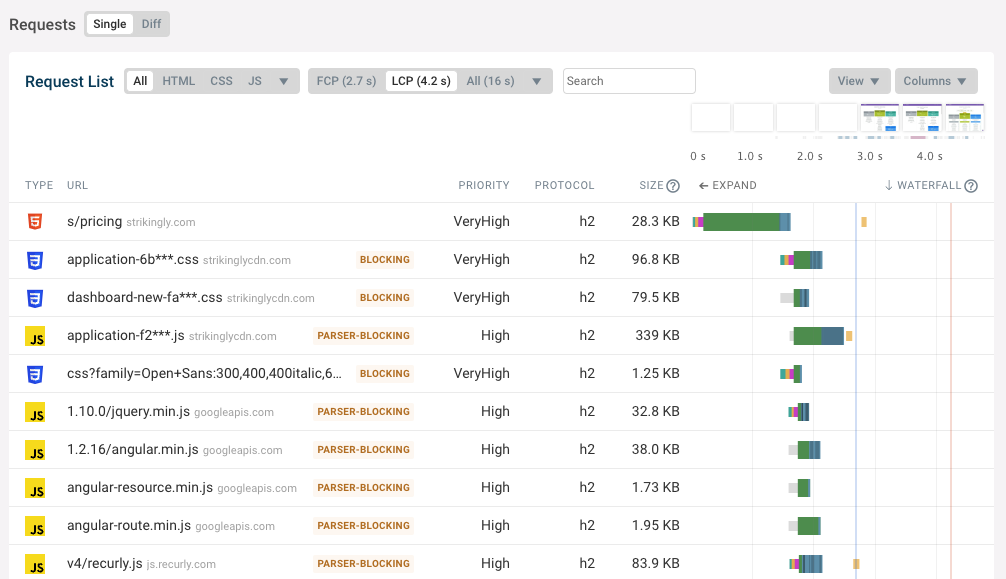

Do You Want to Make Your Website Faster?

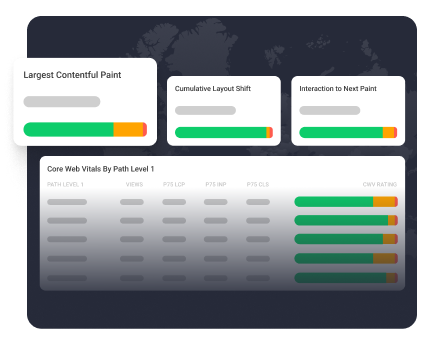

With DebugBear, you can continuously monitor your website from 30+ locations around the world and debug frontend performance issues.

Sign up for our free 14-day trial and gain insight into the performance issues of your most important pages, such as this interactive request waterfall chart:

Monitor Page Speed & Core Web Vitals

DebugBear monitoring includes:

- In-depth Page Speed Reports

- Automated Recommendations

- Real User Analytics Data